Quantitative

Twenty-three participants were invited to respond to complete the PIERS-22 survey. Twenty-two (96%) responded, of which one declined to participate and two did not fully complete the survey. Therefore, a total of 19 (83%) complete responses were captured.

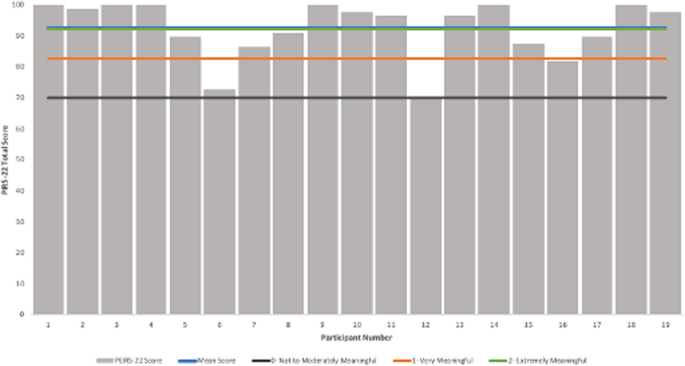

The mean PEIRS-22 score was 92.46 (SD = 9.24). This value is above the “Extremely Meaningful” cutoff point and falls within its standard deviation (SD) suggesting that the level of engagement was extremely meaningful, as shown in Fig. 3. The PEIRS-22 developers recommend that survey users direct their attention to individual scores rather than the group mean score. All individuals provided neutral or positive responses.

Citizen leader and community partner scores for global meaningful engagement, using the modified PEIRS-22

For each of the seven PEIRS framework domains we calculated the mean scores [25] shown in Fig. 4. The highest score was found on the Feel Valued domain, followed by the Team Environment and Interaction, Support, Contributions and Benefits domains. The lowest scores were found on the Convenience and Procedural domains.

Scatter plot of citizen partner and community leader scores by modified PEIRS-22 domains

Qualitative

Individuals from all four groups were invited to participate in interviews as shown in Table 3. A total of 35 participants were invited to join an interview or FG with 22 participants (63%) completing an interview or FG. The community leader group was split into three distinct groups based on site, for a total of six interviews as demonstrated in Table 3. Five of the six (83.3%) invited Site O community leaders, six of the eight (75%) Site T community leaders, and four of the seven (57%) Site P community leaders participated in interviews or FGs. Two of two (100%) citizen partners participated in FGs. Three of the 10 (30%) Site O knowledge users and connectors participated with one representing the PHU and the other two from connector organizations. Two of two (100%) of the methods researchers participated in interviews.

In the following sections are the themes from each of the four groups in the study. First, are all of the themes from the community leader interviews followed by citizen partners, then knowledge user and connectors, and methods researchers. Our intention was to analyze the data for the three sites separately due to anticipated differences in processes and experiences of engagement at the different sites. During data analysis the findings demonstrated overwhelming convergence. Therefore, analysis of the three sites is done together with differences between sites noted. Table 4 provides an overview of the qualitative themes and sub-themes, if applicable, for each group. The interview questions asked about impact and long-term commitment however no themes were identified. Representative quotes for the themes are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Our interpretation of the themes in Table 4 follow. Relationship management is the way that the OPTimise project team interacted with, communicated and shared information. Supporting Processes refer to the facilitators of engagement. Power sharing includes the ways that the OPTimise project team established equitable environments and relationships with participants. Satisfaction with operations refers to how participants felt about technical logistics of OPTimise study participation. The themes were derived from piloting. Sub themes are aspects of the themes.

Community leader themes

Relationship management

Trust

Community leaders reported that having an initial connection from a connector organization, knowledge user, or another community leader helped spark their interest in the study. Community leaders identified that trust building required connection and building relationships organically. Some examples include having conversations not directly related to the research study and showing genuine interest in each other. Another method used for trust building was through one-on-one phone calls and emails between community leaders and OPTimise research team members prior to the group meetings. Throughout the process, there was agreement that the group meeting space was safe and even if a community leader had divergent views, did not feel judged. This safe space helped to build trust especially on a topic like COVID-19 vaccination which already had mistrust associated with it.

Community leaders at Site T shared that in diverse communities building trusting relationships can be more challenging due to historical traumas. Some suggested that the research team could have learned more about the community prior to starting any activities on the engagement continuum to overcome historical trauma and build trust faster. This was emphasized at Site T, where the focus was on Black communities, and it took more time for trust to develop.

Demeanor

The team created an atmosphere described as open, friendly and honest. Several community leaders said that working with the OPTimise research team felt like talking with a friend or neighbor. During meetings there was space for introductions and sharing how everyone was doing personally. Throughout the study, respectful safe environments were created by leading by example. Even when different personalities or perspectives were shared the team would keep the peace by not arguing or debating among themselves. The setting was described as informal but professional.

Overall positive interactions

Overall, trust was built through a series of actions and interactions. Team members made themselves very available to answer questions by phone or email. Meetings were carefully moderated to include everyone. This created relationships where some community leaders said they would miss the team when the study was over.

Community leaders at Site T highlighted that the research team demonstrated learning by ending the study with some slides celebrating Black History Month. This was an unnecessary but positive act that stood out to them and felt authentic.

Supporting processes

Compensation

At site T, community leaders felt that monetary compensation was not the only factor influencing their decision to join the study, but it was appreciated and demonstrated the value of their time and expertise. Similarly, at Site P, monetary compensation was one factor influencing community leaders to join the study by valuing their ideas, opinions and time. But at site P another compensation method was also valued, reference letters to apply for permanent residency status. Two participants at site P also noted that they would not have participated, or reduced their involvement had there been no monetary compensation. The topic of compensation did not come up with site O.

Language

At Site O community leaders identified that research team members who spoke both English and French, as well as a translator, supported their interactions since the community leaders spoke multiple languages. The community leaders also supported the research process at Sites O and P by ensuring communications were culturally appropriate when translated professionally and by speaking the languages of the communities they were engaging. A community leader at Site P acted as an interpreter for interviews, if needed, which they noted was a good learning experience. Language did not come up at Site T.

In-person relationship building

Most of the core research team were based in the same city as site O. This allowed for some one-on-one in-person interactions with community leaders when needed. For example, researchers delivered flyers to some community leaders’ homes for them to distribute into the community. This activity helped build relationships between the research team and some community leaders. At Site T, some community leaders understood that due to COVID-19 in-person activities were limited but believed that the relationship-building would have been stronger had the team visited their community and became immersed in their spaces. This was not directly discussed with community leaders at Site P.

Power sharing

Joining the study

Across the three sites community leaders joined the study primarily through another connection. Several community leaders found out about the study through organizations they work or volunteer for. This connecting organization often provided flyers and discussed the opportunity with the community leader. Many also learned about the study from individuals known to them who were previously part of the study, for example, through a community leader already in the OPTimise study or through connections with the OPTimise research team members. This connection was crucial for some as they initially did not see the value in discussing COVID-19 at that time.

Listening

There was an overwhelming consensus among the community leaders across the sites that they were listened to by the research team. The OPTimise research team asked for feedback, elicited diverse responses, and acted on the feedback they received. Some community leaders indicated that members of the research team were listening to them even when discussing more personal or non-research related ideas.

Power sharing

Across the three sites there was a consensus that all input mattered and was important to the OPTimise research team. At Site O, a community leader highlighted that the team did not act as an all-knowing entity but created a comfortable space for working together. At Site T, the community leaders really felt like they were more than just information sources. There was a need to work together and be leaders since they know their community best. The research team also emphasized the voluntary nature of the work and that community leaders were not forced to be there or continue with the work.

Value and respect

Across all sites community leaders reported feeling valued for their contributions to the study and respected. One participant mentioned being able to see the contributions of the community leaders in the final research recommendations which they interpreted as their contributions having been valued.

Satisfaction with operations

Clarity and detail

Community leaders agreed that they were well informed about the scope and processes of the OPTimise study. They had opportunities for one-on-one discussions to understand the study processes, and had information provided by email as well. The first meeting of the study covered the scope and process of the study as well as the team’s backgrounds. The community leaders reported having minimal understanding of the OPTimise research methodology.

Time

There was a sense that the timing of the study was well-managed. The research team contacted community leaders by email and/or phone to select the meeting time for each monthly meeting. This promoted the flexibility and inclusion of as many community leaders as possible. Community leaders noted that the research team always ended meetings on time. At Sites O and P participants noted that the use of meeting time could have been more efficient and extending the meeting time by 15–30 min could have helped ensure that all the material was fully covered in the meetings. At Site T, one participant noted that they knew people who did not join the study because monthly research meetings were too much of a time commitment, especially for those who were leaders in their communities.

Meetings

OPTimise study meetings for all three sites occurred virtually using Zoom. Community leaders found virtual meetings highly convenient especially around work, transportation and parenting schedules. During the meetings, community leaders liked being able to turn their cameras off. Community leaders appreciated having time to interact and get to know each other especially at the first meeting. Meetings were perceived to be interactive and allowed for open discussions. Breakout rooms were used from time to time and facilitated by a research team member to increase opportunities for sharing.

Communication

Communication included the monthly zoom meetings, email communications and phone calls. One-on-one communications matched the preferences of community leaders. Community leaders at all sites mentioned high rates of communication from the team but were satisfied with the amount. Reminder emails were appreciated for upcoming meetings. Community leaders felt that the research team were quick to respond. Multiple research team members were identified by different community leaders as having excellent communication skills. At Site T, one community leader noted the importance of the meeting minutes to understand what happened at a meeting especially if they had to miss a meeting.

Overall satisfaction

All of the community leaders were highly satisfied with their participation in the OPTimise study. Many found it challenging to give suggestions for improvements due to being highly satisfied with their participation while others indicated that the team learned and incorporated feedback during the study. One suggestion for improvement was to have more OPTimise study community leaders and participant interviews to reflect more of the community.

Community leaders reflected on the following factors which made their experience highly satisfactory: the calming demeanor of the research team who led by example, the willingness to adapt and listen to feedback, the desire of the research team to learn and support the communities, creating a safe space to share different perspectives and the diversity of people engaged.

Citizen partners

The engagement level of two citizen partners in the study can be classified as lead using the Levels of Public and Patient Participation in Health Research classification system for the engagement plan and execution of the OPTimise study. One with an extensive history as a patient and community advisor in research, and the other a nurse and researcher who had previously led other community engagement studies.

Relationship management

Trust

Citizen partners suggested that building trust required discussing and clearly outlining the roles for the OPTimise study especially since many people were part of the study. Throughout the study, good working relationships were built especially during times when a citizen partner brought forward an issue. One citizen partner pointed out that without trust they could and would choose to work on a different study. The PI is key in building trust and creating relationships with citizens engaged in research. One strategy for building trust in this case was having a patient and academic citizen partner on the research team. The citizen partners supported each other with their expertise and discussed together before bringing their ideas to the larger research team and implementing their ideas.

Demeanor

A citizen partner shared that the PI set the tone and atmosphere for the study and building relationships with citizens. The PI needed to be visible and approachable. The PI for this study constantly checked in with the citizen partners and was willing to be adaptable. The citizen partners felt that the PI was cognizant of their time and desire to participate in the study. For example, the PI realized that the scope of commitment for citizen partners increased beyond their initial agreements during grant writing. But the PI consistently checked in with citizen partners to ensure that they were still comfortable with their duties and time commitment.

Overall positive interactions

Overall, the relationship between the citizen partners and the rest of the research team developed positively throughout the study and in different ways as capacity varied. In the first two sites, (sites O and T) the citizen partners led the engagement with the researchers. This involved creating the engagement strategy, working with community leaders directly, presenting with the researchers during meetings and being part of the working groups for the OPTimise study. With the last site, (site P) both citizen partners took on less of an upfront role with the community leaders, but they still felt informed and involved in decisions being made. This led to a united research team inclusive of the citizen partners. Citizen partners felt that the research benefited from a diverse research team with people of varying ages, languages, gender identities and expertise.

Supporting processes

One citizen partner saw their role as a bridge between researchers and the community, the other was a nurse who has conducted post-doctoral research with community engagement. They worked together on developing the engagement strategy for the study and divided up their work promptly (one focusing on site O, one on site T, and both on P with lessons learned from site O and site T).

The citizen partners lead the development of the Community Engagement strategy and agreed that different levels of engagement for community leaders across sites and OPTimise study participants were acceptable based on the activities each community leader was interested in engaging in. Some community leaders wanted different engagement levels in the research process, so the citizen partners and researchers tried to accommodate their preferred level of engagement rather than prescribe it. Citizen partners provided much input and led the engagement strategy for the research. Throughout the study they had to adapt along the way as different communities preferred different levels of engagement.

Power sharing

Joining the study

Both citizen partners had a connection via collaboration on other studies with the researchers on the research team prior to joining. They were both included in grant writing to bring their experience in community engagement to the study.

Power sharing

Both citizen partners agreed that they saw themselves as part of the research team. Although the (non-academic) citizen partner said that it was not guaranteed that they would be part of the team rather it was due to the actions of everyone in the study. They felt like an equal leader and that the team mitigated power imbalances wherever possible by making decisions together in weekly meetings, sharing who led meetings with community leaders, and developing and refining the engagement framework used in the study.

Value

Both citizen partners felt like their contributions were valued. The researchers made it clear that the citizen partners were valued by verbalizing the impact of their contributions and keeping communication open. The citizen partners co-wrote a paper from their perspective on the community engagement aspects of the research study [28].

Satisfaction with operations

Meetings

The citizen partners were engaged in weekly team meetings but did more than just provide advice or guidance on community engagement. They also helped develop slides, supported plain language document creation, communicated with community leaders, and led meetings with community leaders especially at Sites O and T. The weekly meetings also functioned as a form of capacity building of research and engagement skills for the citizen partners by being able to work through challenges faced in the study together as a team.

Time

Citizen partners perceived that there was flexibility throughout the study which enabled them to contribute the time they had. Other research team members could take on more of the work when needed to match the capacity of the citizen partners while still maintaining active engagement for the engagement approach and being informed during the entire study.

Overall satisfaction with operations

The citizen partners reported that the study balanced theoretical and practical applications well. Recruiting people to be community leaders from equity deserving groups was a rewarding experience requiring different strategies for engagement. This led to a nurturing environment where the citizen partners felt like they were learning and working together on ideas pertaining to engagement. Citizen partners were not just being told what to do but led the engagement work through exchange of ideas and decision-making. Citizen partners sometimes had emotional responses from their participation in the study due to feeling the importance of the work and the chance that the community leaders might engage in future research studies due to their positive experiences in this study.

Knowledge users and connectors

For Site O there was another formalized step in the engagement process involving a PHU KU sharing the OPTimise study proposal with Connectors at community organizations. Those connectors then met with OPTimise study staff to learn more about the study prior to making connections between the OPTimise research team and Community Leaders.

Relationship management

The research team connected with the Site O PHU and spoke with the person responsible for community engagement. They got consulted due to the depth of community connection being sought in this study. The PHU KU trusted the research team, so they connected them to connector agencies. Although, ideally had more time been available it might have strengthened the relationships between the PHU and research team and made them deeper.

The connectors felt connected to the research study due to the linkage and endorsement from the KU who they already had a relationship with. Getting the invitation to support the research study from a trusted source facilitated their joining the study. The connectors felt that they played a similar role with community leaders. Since community leaders had a pre-existing relationship with them, the community leaders may have been more likely to join the research study. One area for improvement identified by the connectors would be to provide clearer expectations about their role and their level of engagement with the study. One connector was not aware that after they made connections between the research team and community leaders their engagement would be limited to receiving updates. They indicated wanting to be further engaged throughout the project. This reduced connector engagement to the inform level for the remainder of the study.

Supporting processes

The KU felt that the researchers were genuinely interested in the community which led them to be involved in the OPTimise study. They felt that the warm referral process enhanced the chances of connectors participating in comparison to an email from a researcher unknown to the connectors. Additionally, other factors considered by connectors in deciding to engage in the study were the legitimacy of the study, the ethics proposal, endorsements, compensation for community leaders, and having a concise description of the study to be able to forward to community leaders after an initial phone call.

Another area of improvement related to the process of sharing the study results with community leaders. A clear plan was identified by the research team for writing an academic paper and a brief to be used by Public Health to support their work. However, the connectors and KU were unaware of a summary being shared with the community leaders. Although there was acknowledgment that it may have happened without their awareness or be in development.

Power sharing

The KU and Connectors felt like they were the gatekeepers to the community leaders. Having the steps in the process with the researchers meeting with Public Health and Connectors added protective factors to the study prior to engaging with the community directly. Some of the challenges with the study were the language and terms used were not always the same as the language used on the ground. The language dynamics inherently created an unequal power dynamic. But the research team was accepting of feedback and changed language based on the KU and connectors’ recommendations making them feel valued and listened to and reduced power dynamics.

Satisfaction with operations

Meetings

All study interactions were virtual which was understood since the research was conducted during COVID-19 and virtual meetings were highly accessible for many.

Time

Connectors appreciated that their involvement was limited due to having many other roles and responsibilities. The timing of the study was also supportive because their involvement happened in the summer when many other meetings are not happening. This improved their capacity to be part of the study. When there were changes to study timelines, such as a delayed start due to recruitment of community leaders being slower than anticipated, connectors felt like they were appropriately kept informed.

Clarity

Connectors and the KU felt up to date on the study and that expectations were clearly defined. An area that was less clear was the roles of all members on the OPTimise study team since there were many people engaged although it was not reported to hinder the work.

Communication

Connectors shared that the study was clearly laid out to them by the research team. But it took mental capacity to comprehend due to the complexity of the study. This was seen as a challenge since connectors were already operating over-capacity due to Covid-19 and the nature of their roles. The research team could have worked to have been even more diligent in keeping connectors and the PHU KU more connected to the OPTimise study as it progressed. Responses and updates on the study were reported by connectors and the knowledge user to be professional and timely. Meetings and emails were reported by the connectors and knowledge user to be effective methods of communication. One person suggested creating a supporting document that outlined the names and roles of each person engaged in the study to improve clarity due to the size of the team.

Methods researchers group

Methods researcher participants reported positive experiences with all themes. One noted that they had worked together and with the PI for 10 + years. The methods researchers shared that they viewed relationship building as part of the process of developing trust. The methods group led the development and implementation of the methods for the OPTimise study. They felt that all team members had space to contribute, researcher and non-researcher throughout the study.

link