Integration of team-based learning and simulation-based learning in clinical education of infant feeding and swallowing assessment and management of speech-language pathology students: a retrospective pre-post intervention study | BMC Medical Education

This study adopted a retrospective single-group, pre-post intervention design. The decision to conduct the research was made after the course concluded, and students were therefore not explicitly informed at the time of data collection that their responses might be used for future research. The knowledge tests were mandatory course activities, while the confidence survey was voluntary and presented as a tool for instructor feedback. Both the surveys and tests were part of a standard, low-stakes educational program intended for formative feedback for the instructor, not for summative grading for the students.

Quantitative survey data before and after the placement and test results during the micromodule and after the placement were obtained from Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and Grade centre of the university online learning system ‘Blackboard’ ( respectively. All data was collected in a ‘de-identified’ manner, with no access to personally identifiable information of the students. Therefore, the study was granted with waiving of consent form. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the Joint CUHK-NTEC Clinical Research Ethics Committee (approval number: [2024.392]).

Participants

The study was planned to retrospectively identify data of all students from the final year of a 2-year Master of Science in Speech-Language Pathology in the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Convenience sampling was adopted; therefore, the number of students in the course during the study period determined the sample size. Students who had registered for the course SLPA5305 Work Integrated Learning & Special Clinic II and completed the 4-hour Paediatric Feeding Clinic between 1 st April, 2024, and 31 st July, 2024 were included. Exclusion criteria included students who dropped the course, and students with incomplete test records. All students were adults and no age range limit or gender selection was included.

All students were native Cantonese speakers studying in English. The study involved two distinct data retrieval components. The first was the knowledge assessment (IRAT/TRAT), a mandatory part of the course curriculum, for which data were collected from the entire cohort (n = 40). The second was a voluntary pre- and post-course survey on confidence. A self-selected subgroup of 25 students (62.5%) completed both surveys; this subgroup had an age range of 23 to 40 years (M = 27 years, Median = 26 years) and consisted of 2 male (8%) and 23 female (92%) students. Consequently, the analysis of knowledge gain is based on all 40 participants, while the analysis of confidence is based on the subgroup of 25.

Procedure

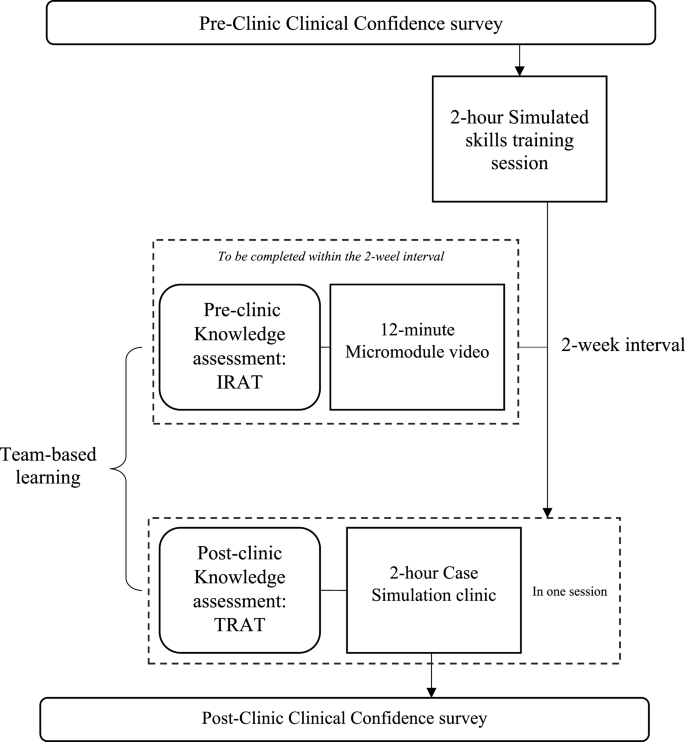

The paediatric feeding clinic consisted of three components: a 2-hour simulated skills training session, a 12-minute micromodule video with IRAT, and a 2-hour case simulation with TRAT using TBL approach (see Fig. 1). This multi-component structure represents an adapted application of the TBL and SBL frameworks, designed to fit within existing curriculum constraints. There was a 2-week interval between the simulated skills training sessions and case simulation clinic, so as to allow adequate time for students to view the micromodule videos and prepare for the clinic.

Flow of paediatric feeding clinic and outcome measures. IRAT: Individual readiness assurance testing, TRAT: Team readiness assurance testing

Simulated skills training session

This 2-hour simulated skills training session covered the basic hands-on skills for infant feeding and swallowing disorders. Details of the session were shown in Table 3. Students were assigned in a group of 9–10 students to 1 instructor. Eight components were included in the session, ranging from general infant caring skills to infant dysphagia assessment and management skills. This session prepared students for the simulation clinic and served as a ‘clinical bridging’ to bridge theories taught in the lecture to practice.

Micromodule

After attending the simulated skills training session, students would receive a 12-minute micromodule video, in which they learn the observation skills during bottle feeding for two infants. Students were required to view the micromodule individually online and completed a knowledge test after viewing the micromodule. Infant dysphagia assessment skills, including counting suck: swallow ratio, sucking rate, number of sucks per sucking burst and signs suggestive of respiratory compromise were demonstrated in the video. A knowledge assessment test, Individual Readiness Assurance Test (IRAT) [17], was adopted after viewing the micromodule video, on the university online learning platform ‘Blackboard’. This part prepared students for the case simulation clinic 2 weeks later.

Case simulation clinic with team-based learning approach

After a 2-week interval, students attended a 2-hour case simulation clinic using TBL approach in a group of 5–6 students. Before the start of the simulation, the knowledge assessment test in group format, Team Readiness Assurance Test (TRAT) [17] using the same questions as in the IRAT, was implemented. Immediate feedback and clarification were given based on the results of IRAT and TRAT. This aimed to consolidate the knowledge learnt and clarify misconceptions before the simulation started.

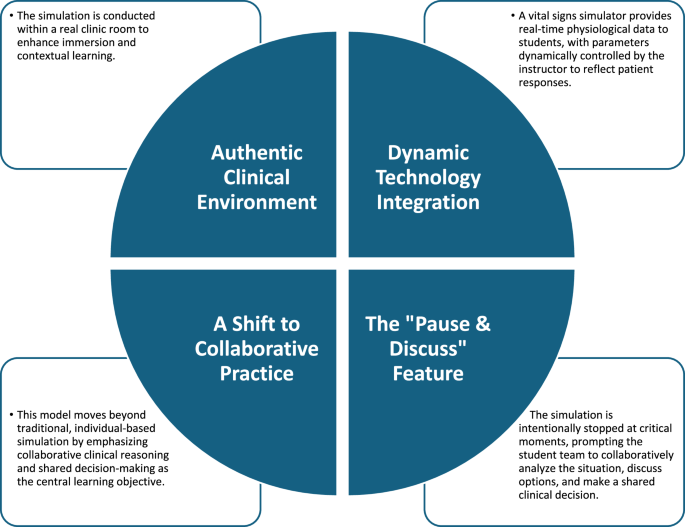

The clinic format was a hybrid simulation mode, which involved the use of one low fidelity infant mannequin and one simulated caregiver. It was conducted in a real clinic room at the University speech therapy clinic to improve immersion and contextual learning. During the simulation clinic, students played the role of SLP and were required to implement a clinical bedside swallowing evaluation for an infant aged 35 days and complaint of choking. The specific learning goals include: (a) conduct a comprehensive case history interview with the simulated caregiver; (b) perform an appropriate oromotor and non-nutritive suck assessment; (c) accurately observe and interpret the infant’s physiological and behavioural cues (e.g., desaturation, coughing) during a feeding trial; and (d) collaboratively select and trial at least one appropriate intervention strategy (e.g., pacing, elevated side-lying).

Dynamic technology integration was employed. Computerized application of paediatric patient monitor simulator, namely PEDS VITALS [24], was used to provide the instant display of vital signs of saturation level, heart rate and respiratory rate of the low fidelity mannequin throughout the session. The monitor simulator was controlled with another tablet device by the instructor. Additionally, the clinical signs of the infant mannequin were narrated by the instructor verbally to the students (e.g. “The infant is coughing, Pulse oximetry is reading 80% SpO2.”).

A notable feature of this simulation clinic was the incorporation of a team-based learning method that fostered discussion and collaborative learning. A transition towards collaborative practice is occurring. Rather than traditional individual clinician simulations, the clinic operated on a team-based model, emphasising collaborative clinical reasoning and shared decision-making as the primary learning objective.

During the simulation (i.e. step 5: Clinical problem-solving activities in TBL), the “Pause & Discuss” feature was utilised. Students were permitted to ‘stop’ the simulation at their discretion to confer with their peers regarding the subsequent steps of assessment or intervention. They were encouraged to use a ‘think aloud’ protocol to verbalize their clinical reasoning as a team. Feedback during this step was primarily peer-driven, facilitated by the unique ‘pause and discuss’ feature, with formal, summative feedback being reserved for the debriefing phase (Step 6). For example, when students noted desaturation while feeding using a large-orifice teat, they may ‘stop’ the simulation to deliberate on further interventions before doing another experiment. Figure 2 illustrates the key features of the case simulation clinic.

Key features of case simulation clinic

At the end of the session, debriefing was held. Students could reflect on their own clinical skills, clarify any misunderstandings and summarize the case study. For the detailed steps of TBL and SBL in paediatric feeding simulation clinic, refer to Table 4.

Data collection & measures

Data was extracted via two systems to assess students’ knowledge and clinical confidence on infant dysphagia. All data was collected in a ‘de-identified’ way, ensuring that no personally identifiable information about the students is accessed or disclosed. To ensure confidentiality and enable pre-post linking, a non-identifiable code was assigned to each student for data matching, after which all data were fully de-identified by an administrative staff member not involved in the research prior to analysis. Students’ demographic data of age and gender were provided by the division clerical staff in an anonymous format.

Knowledge assessment (IRAT and TRAT)

Students’ knowledge was assessed using the assessment method of TBL assessment. The test consisted of 6 multiple-choice questions regarding infant dysphagia assessment (See Appendix A). The IRAT and TRAT questions were identical, following the framework of TBL by Burgess, van Diggele [17], in order to precisely assess students’ knowledge change. Students were required to complete the IRAT after the simulated skills training session and viewing the micromodule video; and complete the TRAT at the end of the simulation clinic (See Fig. 1). Scores of IRAT and TRAT were extracted from the university online learning system ‘Blackboard’ (.

Clinical confidence survey

Students’ clinical confidence was measured via a self-rating survey. Students were asked to fill in the survey before the simulated skills training session and two weeks after the clinic to measure their clinical confidence. Each student was given an unidentified identity number for the course to ensure anonymity. The survey utilized the Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) platform and consisted of 20 questions with a 5-point Likert scale response (See Appendix B). The questions were developed based on five out of seven areas in Competency Based Occupational Standards (CBOS) as students’ clinical competency was assessed by CBOS throughout the clinical placement curriculum. Each area comprised of 4 questions regarding students’ confidence on that area. Students rated on a 1–5 scale (1 = not confident at all to 5 = very confident). All survey responses were anonymous. Only data of the eligible students was collected through Qualtrics.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic data of the students. As the data were retrospective, their normality of variation was unknown. Therefore, the normality of variations between pre- and post-knowledge test scores were assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, to determine whether to use a parametric or non-parametric test. As calculated, the difference between pre- and post-clinic knowledge test scores, D(40) = 0.21, p <.001, was significantly not normally distributed. Therefore, non-parametric related sample Wilcoxon signed rank test was adopted. Due to small sample size of subgroup (n = 25) in both knowledge test scores and level of clinical confidence, non-parametric related sample Wilcoxon signed rank test was employed for its analysis using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28). Statistical significance was set at a p-value of < 0.05 for the score of knowledge test and total score of clinical confidence questionnaire. Bonferroni correction was adopted to adjust the significance level for the five sub-categories under the clinical confidence questionnaire, and their corresponding significance level was therefore set as 0.01 (0.05/5) to reduce type I error. Effect size, r, was calculated and compared using Cohen’s d classification to measure the magnitude of the difference before and after the clinic [25].

link