Re-drawing the map: a case study of decolonized research methods & methodologies | International Journal for Equity in Health

Research principles

The crux of establishing the decolonized approach was the formal and informal meetings held with the Community Advisory Committee (CAC). The first CAC meeting was dedicated to detailing the logistics, process, and methods that would be applied to the research. The meeting began with a discussion of the principles of decolonization and Indigeneity in the community, and how these related to the study goals. The research team came to a shared understanding that decolonization as a principle meant working to undo the lasting impact that colonialism and apartheid had on their day-to-day lives. The practical application of this was the decision to create a “Freedom Park” way of doing research, that focused on community needs and realities, and allowed people to speak about their own experiences safely, acknowledging the influence of existing and historical systems of power.

CAC members also shared the complex relationship to Indigeneity and Khoisan heritage present within their Coloured community. There was a collective recognition that the Coloured community has “Khoisan forefathers”, although their relationship to that heritage had been intentionally eradicated throughout apartheid. One committee member shared a story about how, as school children under apartheid, they had been taken to museums where they were shown deformed skeletons. They were told these skeletons were Khoisan. Teachers emphasized the skeleton’s lack of humanity, unappealing appearance, and low status in the apartheid racial hierarchy, asking the children if they thought they were as horrifying as the skeletons. The intent was to encourage Coloured children to no longer self-identify as Khoisan, something associated with being grotesque, or “inferior”. Exhibitions of this type that perpetuated the racial stereotypes and hierarchies of the apartheid government were not uncommon during this time period [28]. CAC members emphasized that while their history was important, they were still in the process of reclaiming it for themselves, unlearning, learning, and teaching their children about their heritage.

Through this discussion it evolved that decolonizing the research was not about returning to historical Indigenous ways of knowing, but of understanding the contemporary context and realities of life in Freedom Park, and how they are influenced by a history of trauma and oppression. This discourse laid the foundation for how to approach the development of the research framework and data collection methods.

The research team discussed the importance of framing this initial study as the first of many, with the end goal being a community-owned solution to the identified SRH issue. The CAC emphasized that seeing the bigger picture of the work was important both for their planning, and for what they communicated to the community. One CAC member described the process, saying “This planning process is planting a seed, and now we will water it. The more we water it, the more it will grow, and bloom, and turn into something strong and beautiful.”

Research method

The research team then turned to the identification of an appropriate research method. CAC members developed criteria the data collection method must have to be an appropriate tool for the community. The data collection tool had to: (1) prioritize personal perspectives, allowing young women to speak for themselves; (2) be collaborative and participatory; (3) create action strategies; (4) be creative and engaging; (5) provide privacy to reduce the risk of gossip, and; (6) reduce discomfort in talking about personal and sexual topics.

The researcher provided examples of data collection methods for discussion, (see Table 1) informed by common data collection methods in decolonized SRH research [6]. The opportunity was to modify, combine, or create an entirely new approach to data collection. The CAC discussed the positives and negatives of each method in relation to their criteria. Their assessment of the utility of each proposed data collection method in alignment with their criteria can be seen in Table 1. The CAC also discussed how each method would relate to AGYW’s communication norms. Body mapping aligned best with the criteria, but the CAC opted to modify the approach to create a unique method that would be more appropriate to local norms, provide more privacy, and reduce the risk of gossip for the AGYW participating.

Unique “third person” approach to body mapping

Body mapping emerged in South Africa as a form of therapy and data collection for women living with HIV/AIDS. It was first implemented in Khayelitsha township in the post-apartheid era [29], and continues to have a significant presence in the country. CAC members were already aware of its existence and were familiar with the approach.

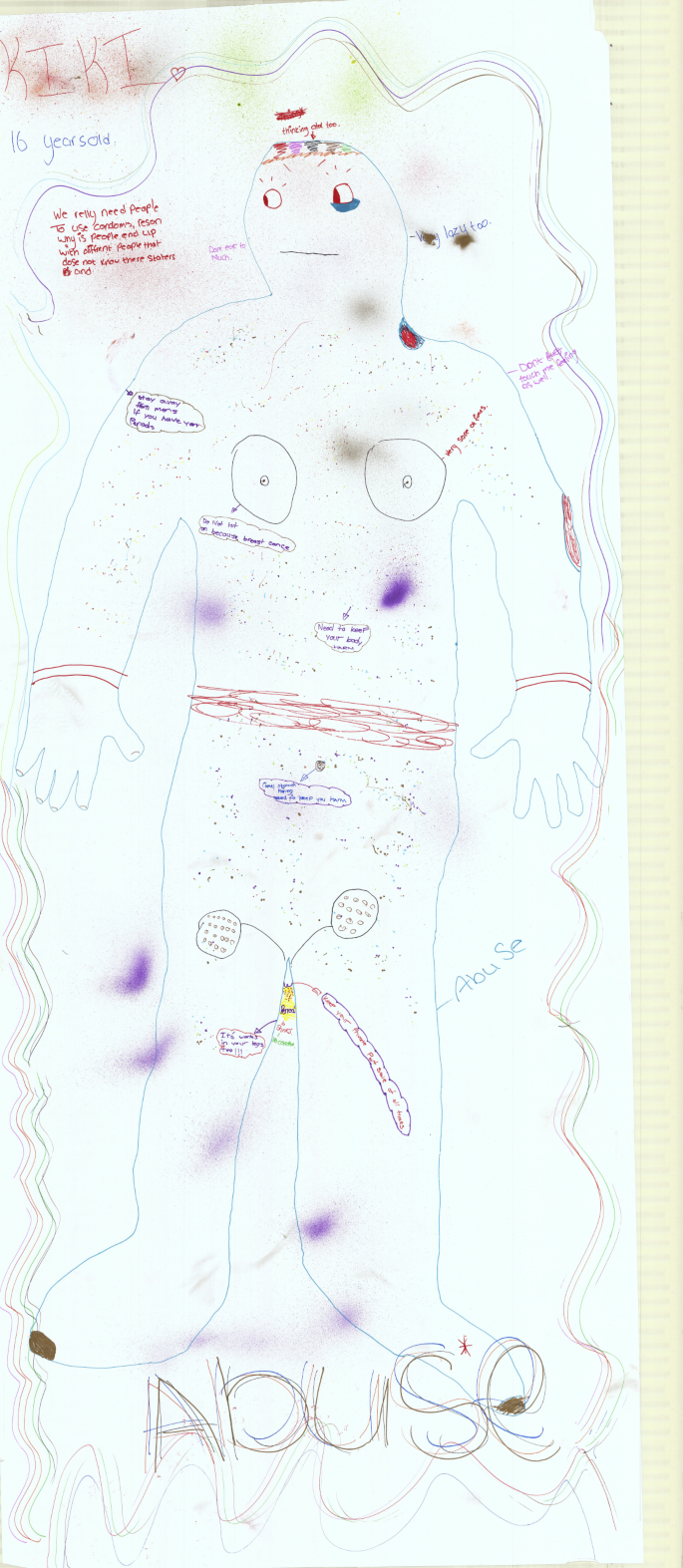

Typically, body mapping provides the opportunity for an individual to illustrate their personal experiences and emotions. The CAC modified this approach, asking AGYW to partner up and draw a body map of a third person who represented a “woman in Freedom Park”. This meant that the map would not be explicitly representative of an individual’s lived experience, but rather informed by multiple experiences. To make it clear that the map was a different woman, they would give a name and age to the illustration, as seen in Fig. 3, an example of a body map from a workshop. The partners would then work together to answer prompts on SRH topics. They were able to pull anonymously from their own personal experiences, or the experiences of families, friends, and community members.

Example of a group body map

The modifications made by the CAC meant that AGYW could provide personal insights anonymously to prevent gossip; work collaboratively to discuss common SRH issues; and provide forward-looking action responses, both through the maps and their narratives. The activity would create space for art and creativity and allow young women to bring up sensitive SRH topics through drawing and writing to reduce discomfort. This approach to body mapping in the “third person” appears to be unique in the literature and represents an approach that moves from the individual body, to the collective body.

Workshop design and implementation

Co-design of workshop framework

At the following CAC meeting the research team detailed workshop logistics, and co-designed the workshop implementation process. The discussion focused on how to introduce the adapted body mapping approach to ensure participants were receptive and open to active participation.

The priorities of the CAC when co-designing the workshops were (1) personal safety of the participants; (2) participant comfort in discussing topics related to SRH; (3) active participation; (4) participant understanding of the creative freedom of the body mapping approach; and (5) clear prompts to gather insights on SRH priorities. They also emphasized the importance of appropriate incentives for participants. The decision was to offer snacks and drinks during the workshop, lunch at the end of the workshop, and an airtime voucher of 30 Rand.

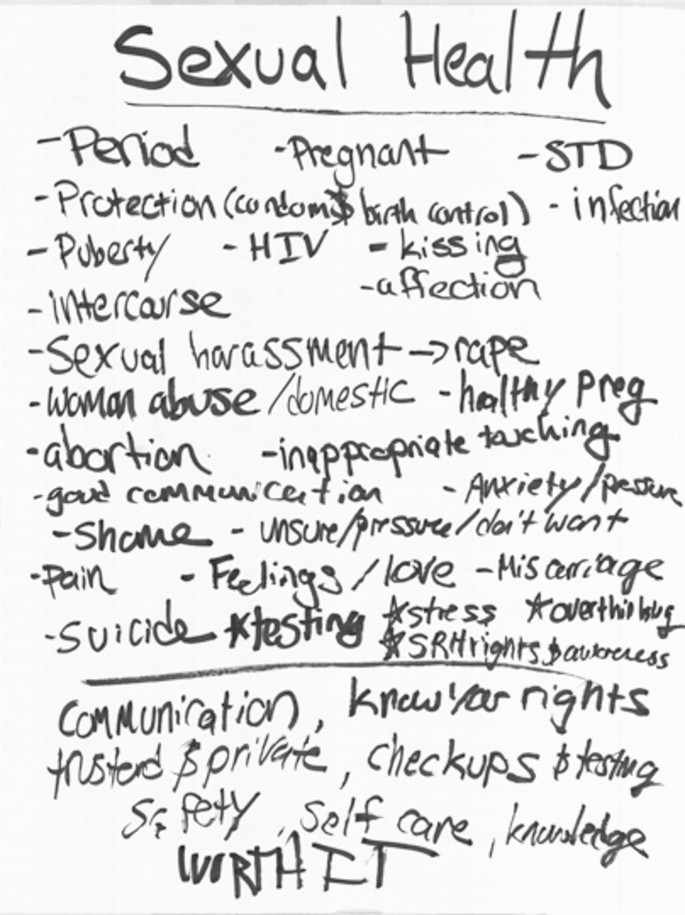

To activate participants, the CAC proposed starting the workshops with an icebreaker, designed to create a sense of familiarity, shared experiences, and invite physical movement and engagement. Next, to build comfort discussing SRH topics, the research team proposed guiding participants through the creation of a shared SRH “dictionary”, or collection of terms and concepts that qualify as SRH (see Fig. 4 for a sample dictionary).

Example of an SRH dictionary

Developing body mapping activity

The CAC then discussed how body mapping could be presented to participants. They opted to create talking points for the workshop facilitator. The facilitator would discuss with participants the potential forms of artistic expression that could be used (drawing, writing, ripping paper, etc.), what participants might want to draw on the body (SRH outcomes, feelings, root causes, etc.), and have participants explain the meanings and use of different colours.

Finally, the research team identified three prompts for the facilitator that would address the underlying research question around priority SRH needs. The prompts asked participants to: (1) Draw the parts of the body that have to do with SRH, (2) Draw the SRH issues that are most common in Freedom Park, and (3) Draw the number one SRH issue you would like to see addressed in Freedom Park. While participants were drawing, the researcher and research assistants would visit each group, answering questions, providing additional prompts, and asking participants to describe and explain elements of their drawings in greater detail.

Knowledge sharing & implementation

The CAC established the importance of an equal exchange of information. Participants were offering up time and knowledge, and the research team felt it was important to offer knowledge in return. Participants were informed that once priority SRH issues were identified, experts would be brought in to host educational series on these topics for any interested community members, after which participants could join additional workshops focusing on problem solving. Details of these educational and problem-solving workshops will be explored in future research.

Ultimately, between April and May of 2024, seven 3-hour workshops were held. Fifty-four AGYW, aged 16–25 attended, all of whom identified as women, and lived in Freedom Park full time. The findings from the workshops are detailed elsewhere, as this study focuses on the decolonized methodologies, co-design process, and methodological findings.

Data analysis

All members of the research team participated in the analysis and interpretation of the body maps. The role and mode of data analysis that the different research team members were responsible for can be seen in Table 2. This was critical in applying a culturally relevant lens to the extracted themes.

At the end of each workshop, the RAs met with the primary researcher and discussed the findings from the workshop while it was fresh in their minds. Following the workshops, the primary researcher digitized the body maps and removed any identifying characteristics, before presenting them to the CAC at an analysis and interpretation meeting. CAC members conducted in-depth visual analysis, interpreting the meaning of shapes, drawing styles, and assessing how the maps reflected community norms. They also identified linguistic and culturally contextual points that were vital to the analysis. One example is the use of the word “overthinking”, which in their community typically referred to suicidal ideation, rather than anxiety. The analysis conducted with the CAC provided the parent themes used for final data extraction.

Discussion & implications

This study explored the process of applying a decolonized research methodology, and the resulting adaptation of a data collection method specific to community needs. Findings from the application of decolonized research methodologies are identified, providing guidance for other researchers.

Centering the community

Research as reciprocal

The research team emphasized the importance of an equal knowledge exchange between community participants and researcher. Western academic research strategies often focus on the extraction of data, repeating colonial practices of taking resources to benefit themselves, without considering the needs of the community [3]. The principle of reciprocity in research is emphasized in decolonial literature as a strategy to uplift and empower communities, changing participants from “the researched” to an equal partner in the research, by ensuring that both participants and researcher gain value from the research process [3]. A priority in this study was arranging relevant subject-matter workshops to offer a trade in knowledge to the community on topics requested by participants, engaging the entire community in this reciprocity of information. Reciprocity was further pursued by ensuring that research team members were adequately compensated for their labour.

The research design prioritized an equal exchange of personal knowledge and vulnerability between all members of the research team, and created mutual opportunities for reflection. CAC members shared personal experiences with apartheid, research, and community communication norms, reciprocated with personal experiences from the outsider researcher. Outsider researcher refers to an individual who is a cultural outsider from the community of focus. Outsider researchers are prompted to be reflexive, critiquing their own biases and motives throughout the research process [30]. However, this approach centers the researcher, rather than the community. The equal exchange of knowledge through an open dialogue of self-reflection and vulnerability in this study ameliorated the complexity of outsider research status, centered the community in the reflexive thinking, and moreover, allowed for different levels of reciprocal knowledge sharing throughout the research.

One CAC member reflected on their impetus behind participating in this research process saying “I’ve been working since the age of 9 years old. I know what it’s like. We can bring [the participants] hope, but hope depends on perseverance and commitment. Hope can only be action once you play that action into real things. And it is going to take effort.” This sharing of motivations and experiences created greater trust, and enabled collaborative research, done with the community rather than to them.

Transparency creates trust

The study sought to create an environment of transparency both within the research team, and with the community writ large, regarding the research approach and both short and long-term goals. Removing a traditionally hierarchical structure, and offering an equal exchange of knowledge, both academic and personal, built a deeper and more equitable relationship between the community, research team, and researcher. This created a more even playing field, and a greater sense of trust and respect. We found that this made the collected data deeper and richer, ascribed greater value to the knowledge and contributions of community members, centering their voices more directly in the work [31].

Critiquing power structures

A justice based approach to research

The principle of justice focuses on counteracting the imbalances brought about by historical and contemporary oppression to create equity, and is therefore a key component of decolonized research [32]. Particularly as referenced in the San Code of Research Ethics, a justice-based approach to research ensures that community influences and opinions are held at an equivalent if not greater value to those of the dominant Western research culture [27]. This approach provided a framework for the research team to acknowledge and address the power imbalances that are prevalent both in traditional research, and in Freedom Park- between researcher and community stakeholders; between Western research methods and local ways of knowing; between academic institutions and community organizations; and between white and Coloured populations, amongst others.

The non-hierarchical structure and co-design research processes used in this study were critical in challenging the power imbalances common in Western research practices [33]. The co-design process and regular checkpoints with CAC and RAs ensured community leadership on research processes, and balanced decision-making power. In particular the joint creation of research methods and methodologies that incorporated local norms and epistemologies was a pivotal component of this justice-based approach. The incorporation of culturally relevant research techniques redresses power imbalances inherent in academic research, both between researched and researcher, and in the choice of research methodologies [34].

Communication, care, and asking the right questions

Traditional Western research practices mandate that the researcher is removed and objective, keeping an intentional distance, with a practice of non-interference. However, the open, flexible, and even informal channels of communication between researcher and community members in this study contributed to greater equity throughout the research [35], and challenged the hierarchy and power imbalances inherent in many Western research models [31, 36]. This changes the role of community members from passive sharers of knowledge, to mutual participants [3]. One of the greatest challenges to unequal power systems and hierarchies is representing the humanity of all people involved.

The fluid communication style used in this study opened the door to more quotidian discussions regarding how daily life is influenced by power imbalances and historical intervention. Open discourse regarding existing power structures also plays a key role in challenging them- leaving them unspoken lends to their power. Discussion and recognition of the ongoing impact of colonialism and apartheid on health, SES, safety, housing, patriarchal norms, and more, was vital to the development and implementation of the research. An open discourse with reflexivity, transparency, and communication throughout the research process allows feedback to be heard and incorporated into the process itself [36]. It is for that reason that ongoing recognition of historical and contemporary outcomes of colonialism and unequal power structures is a key component to ensuring they are addressed and redressed in the research process, methods, and outcomes.

Challenging western research foundations

Community-designed data collection methods

This study highlights that using a decolonized approach to identify appropriate and culturally relevant data collection methods enhances the validity, credibility, and applicability of findings [3, 11]. Use of western methodologies in health research dominates academic literature and modes of thinking [37]. Co-creation of research methods and equal valuation of systems of knowledge critiques the concept that dominant Western research strategies are the only effective and appropriate approaches to research. In this instance, the application of decolonized methodologies and community co-design processes resulted in an adapted body mapping approach that was efficient, effective, and widely accepted by the community.

Body mapping is an empowering process that gives participants greater control over their stories and experiences, and enables outsiders to better understand the perspectives of populations who are frequently marginalized [38]. The modified “third person” approach to body mapping may in part be seen as the CAC reflecting the collectivist identity present in Coloured communities such as Freedom Park [39]. Collectivism values community support, and interconnectedness with family (where family is an extended definition beyond blood relations) and community, rather than the personal independence of individualism. The unique “third person” body map challenges the Western norm of individualism that is often perpetuated through traditional research practices and data collection methods. An individualist perspective on data collection and knowledge translation may overlook key insights from communities when used in a collectivist context, where knowledge is relational to other individuals and experiences [40]. This adapted approach to body mapping speaks to the value of community-designed culturally appropriate data collection methods to account for the unique epistemologies of communities, in contrast with pre-determined data collection methods that perpetuate neo-colonial epistemological and individualist perspective dominance in Western research [41].

Further, this adapted approach speaks to the identification of the body as a construction of the social and political environment in which it exists [42]. The findings of the primary research represented SRH as something that cannot be separated from the local socio-economic and political context [15]. The CAC’s creation of a “third body” or body politic, can be seen as a reflection of these findings. Other researchers, in particular researchers working to incorporate arts-based research into their global health praxis may find the application of this data collection method, or the strategies used to develop it, useful in their approach to decolonizing the traditional research process.

This adapted data collection method was highly accepted within the community. AGYW were extremely engaged with the process through each workshop. Participants were creative, introspective, and despite the intensity of the subject matter, they laughed and told stories more freely while drawing on the body maps. One RA summarized this by saying “I noticed that in the workshop today, they found it very difficult to communicate to you, vocally, but they could draw it out. And once they were drawing it, they could express more.” This, alongside the precautions taken to prevent gossip, allowed participants to discuss and share feelings and knowledge on a range of topics that might otherwise have seemed taboo.

Limitations

There were some limitations in this study that further enforce the lessons learned and best-practice recommendations for other researchers. One limitation of this study was the power imbalance created by the primary (outsider) researcher providing compensation. While fair payment for labour is an essential component of reciprocal research, it nonetheless creates an inherent imbalance between members of the research team. This was mitigated in part by placing the question of reimbursement amounts, types (e.g. financial or otherwise), and timing in the hands of the CAC. Further, while the “third person” body mapping was effective in increasing privacy, Freedom Park is nonetheless a small community, and fear of gossip may have prevented participants from joining, or from being fully transparent. Those who did participate were frank and open, but it is a significant risk that others with different experiences may have been wary of participating.

An additional limitation is that the summarizing and interpretation of findings, even when guided by community members, nonetheless reduces the ability of the participants voices to be directly heard. While quotes and images have been shared in the primary research, this limitation should encourage other researchers to explore additional avenues that allow participants, especially AGYW, to speak on their own behalf.

Finally, because this study was a unique attempt at applying decolonizing methodologies to an SRH study, utilizing new data collection methods, there were certain methodological limitations in the form of limited standardized protocols for delivery. This further emphasizes the recommendation that more information and guidance on the application of decolonized research methods be shared by researchers.

Conclusion & what comes next

This study shows how the application of decolonized research principles results in a culturally appropriate and transformative research process. The research exemplifies how these strategies can be used to effectively center the community, address power imbalances, and recognize other ways of knowing. Through this process the importance of self-determination emerged as critical for community empowerment. The emphasis on community co-creation was an opportunity to acknowledge and critique existing power structures, while simultaneously developing an appropriate and applicable research process that recognized other ways of creating, interpreting, and sharing knowledge.

To support the increased application and use of decolonized methodologies by other researchers and practitioners, this study has identified several best practices and practical strategies derived from this study. These recommendations can be found in Table 3.

These practices reflect not only theoretical commitments to decolonization and justice, but practical strategies for embedding community voices, epistemologies, and leadership into all phases of research.

The authors believe that this research supports their work to advocate for the greater use of decolonized research, as a strategy to benefit communities in need, and create a shift in the way research is conducted that acknowledges and addresses many years of harmful practices. This work aligns with wider calls for approaches to adolescent sexual and reproductive health that focus on a re-centering and redistribution of power towards greater mutual accountability, collaboration, and prioritization of non-Western ways of knowing and leading [43]. We further propose the ongoing creation of exemplars that guide not only the questions we must ask ourselves as researchers, but demonstrate their application in the work, and the benefits they bring.

link